Inwood’s Jazz Power Initiative Puts Community-Driven Music Education Center Stage

The nonprofit’s co-founder Eli Yamin spoke about the importance of making jazz education accessible Uptown.

By Brandee Sanders

October 01, 2025

For Uptown jazz composer and educator Eli Yamin, the arts are a vital element of community building. From the nighttime Newark jam sessions he performed in as part of his mentor Amiri Baraka’s Kimako’s Blues People series to his global travels as a Jazz and Blues Ambassador for the U.S. Department of State, Yamin has witnessed the connective power of artistic creative expression throughout his storied career.

As the managing and artistic director of Jazz Power Initiative—an Inwood-based music education nonprofit he co-founded with Clifford Carlson—Yamin is cultivating spaces for community members to share their stories through the performing arts. Founded in 2003, the organization leads free and low-cost intergenerational jazz-inspired programs and community concerts for youth, educators, and lifelong learners in Washington Heights, Inwood, Harlem, and the Bronx.

Columbia Neighbors spoke with Yamin about the mission behind Jazz Power Initiative, the nonprofit’s Uptown roots, and the importance of arts education advocacy.

When did you develop an affinity for music? Who are some of your early musical influences?

I started playing the piano as soon as I could reach the keyboard. Music was very important to my family. It was kind of like our family religion, and we leaned on the art form as a source of support. When I was very young, my parents had a reel-to-reel tape player, and they would play a recording of Elizabeth Cotten. She was an amazing folk musician from North Carolina with a raspy voice and scratchy fingers on the guitar. Her music was soulful, and you could feel it in your bones. In terms of my connection to the blues and love for African American art, that’s where it began.

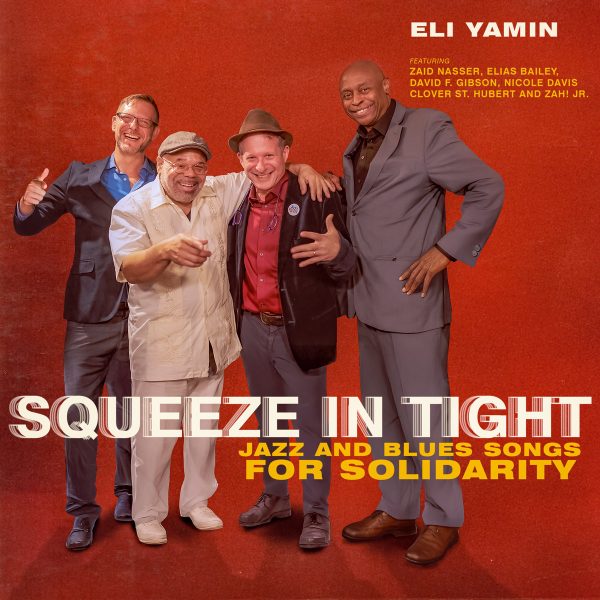

Pete Seeger, another folk music legend, also had a huge influence on me.I got to see him perform and loved his storytelling, collaborations with artists like Lead Belly and Woody Guthrie, and his deep connection to American folk music. Elvis Presley’s Heartbreak Hotel was also a window into blues for me and inspired some of the music on my new album Squeeze in Tight: Jazz and Blues Songs for Solidarity.

My mother also had a collection of B.B. King and Jimi Hendrix records that were really important to me and deepened my understanding of blues and rock ‘n’ roll. In high school, I got to know the work of Thelonious Monk, Count Basie, and Duke Ellington, and that’s when I really got deep into jazz.

Were you involved in any arts education programs growing up? Did you have any mentors who shaped your perspective on the arts?

During my junior year of high school, I was part of a program called the Summer Arts Institute at Rutgers University. In that program, I met kids from all over New Jersey who were passionate about the performing arts. I connected with a few folks from Newark who were attending Newark School of the Arts, and we formed a band. Throughout my senior year, we performed all around the city of Newark, and I witnessed the cultural connectivity of Black arts and loved it. Summer Arts Institute was really seminal because if you aren’t in an arts-focused school, it can feel isolating. It provided me with an amazing sense of community.

Throughout high school and college, I had amazing educators who opened doors for me in music, like Harry Pickens (who is a great pianist), Kenny Barron, Keith Copeland, and Jaki Byard.

Midway through my studies at Rutgers, I met Walter Perkins, a great drummer from Chicago who was living in Queens. His music credits are historic. He’s worked with everyone from Harlem’s Carmen McRae to Charles Mingus Jr. He was an incredibly generous man who opened up his heart to me and became like a second father. I played in his band when I came out of college, and we had a very close relationship until his death in 2004. He was an important mentor and guide, and I’m so grateful for him.

When did you realize the arts could be used as a means for community building?

Before meeting Walter, Amiri Baraka was one of my mentors. I met Amiri when I was working at the WBGO radio station in Newark. It was unusual for a 19-year-old kid to be so deep into traditional jazz, so he took an interest in me and we developed a friendship. He used to host community performances at his house called Kimako’s Blues People, where my band and I performed, and that’s where I got introduced to the world of Black arts in different forms: music, dance, theater, and poetry.

Amiri became a role model for me. He was an incredible artist who was always organizing community-facing activities. He would always carry flyers for events to bring the community together. It left a huge impression on me as far as how I could be an artist who is about serving the community and keeping it grassroots. I saw how much he cared. It showed me the arts have to be available and accessible, and it takes people who care about it and hard work to make that possible.

What inspired the creation of the Jazz Power Initiative?

I was a guest artist at the Louis Armstrong Middle School in Queens and the musical director for one of their annual performances. The school’s theatre teacher, Clifford Carlson, and I realized the traditional musicals didn’t resonate with the students. We also realized that although the school had Louis Armstrong’s namesake, the kids didn’t really know much about him, or jazz for that matter.

So we started to write jazz musicals inspired by stories that were relevant to these children’s lives. We wanted to use original jazz music grounded in tradition as a way of storytelling.

I learned from Amiri that jazz isn’t just music, it’s a great way to tell stories. It’s dance. It’s theater. It’s poetry. Clifford and I wrote five original jazz musicals in five years and produced them at the school. We had 50 kids in each cast and performed it for 1,700 students who loved it.

We realized this was a miracle and decided to form a nonprofit to continue producing jazz musicals at public schools in New York City. We started the Jazz Drama Program in 2003, which later became Jazz Power Initiative, and we decided to put down our roots Uptown. We founded the organization as a way of using the language of jazz to tell stories that are relevant to students’ lives.

Can you share your thoughts on the importance of having arts education nonprofits in neighborhoods like Inwood?

I did 10 tours for the U.S. Department of State as a jazz and blues ambassador. I saw how many more resources there were for arts education in countries like Montenegro and Russia. When I worked at Jazz at Lincoln Center—where I stayed for 10 years before focusing on Jazz Power Initiative full time—we were bringing kids from Harlem, Washington Heights, the Bronx, and even Brooklyn to Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

It was a great experience for the students, but it was hard to get kids from Uptown and other areas to travel downtown, oftentimes due to financial constraints. Sometimes a kid would have to leave the program, and I’d meet with their parents and find out it was because they didn’t have enough money for the subway.

That motivated me to bring high-quality arts instruction right up to the neighborhood. Having arts education programs right here in their community is their birthright. Jazz music, African American music, and Latin American music were created in these communities. They deserve access to their inheritance.

We have so many great artists in the community; there’s no reason why kids should have to travel far. In order to make the education aspect of it effective, you’ve got to have great artists leading it. We have local artists who hold the treasure of knowledge around music. We have to value them, pay them fairly, and give them a platform to share their knowledge in a dignified way that supports and uplifts their communities. We need community-based organizations to employ them.

Aside from that, a lot of the educators are musicians, and we at Jazz Power Initiative want to make sure they have spaces and venues where their work can be presented in a way that is appreciated. So we started producing low-cost community concerts. We’ve also added adult education workshops to our offerings.

What are your thoughts on the current state of arts education programs in public schools?

Arts programs often get cut in public schools due to shifting priorities. We should hold our leaders accountable for making those decisions.

Artistic training supports the growth of the whole child. There’s so much research on music education and how it lights up parts of the brain. There are so many life lessons learned through music. You learn how to synchronize with others, you learn how to listen, you learn how to get in touch with your emotions, and you learn a lot about yourself.

Even if our students don’t pursue music as a career, we want to keep supporting them in finding ways to make the arts part of their lives. One of our students is an amazing singer from Brooklyn who is an EMT now, and he sings to people in the ambulance. That’s beautiful to me.

We want our kids to know the arts are a source of strength and a way of connecting with their community. You can grasp hold of this great music tradition and lean on it when you need it, and share it when others can benefit.

We really need to make a strong case for bringing the arts back in a very serious way. It could help us address a lot of the challenges we’re facing in education. We’re doing our part at Jazz Power Initiative through leading residencies at New York City public schools and offering low-cost programming, but we can’t replace the full-time music teachers and the bands, choirs, and orchestras in these schools.

Music changes lives. We have to make it accessible for our younger people Uptown so they can shine and thrive.

How are you channeling Uptown’s rich legacy of jazz through the programs and initiatives you’ve organized?

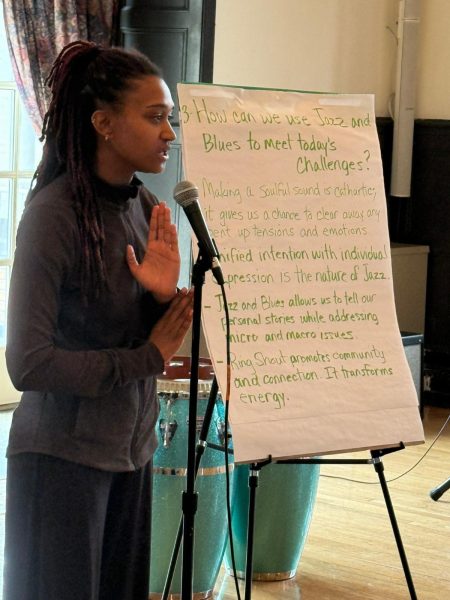

We center African American and Latin American cultures in all of our programs. It’s the foundation of all that we do. We’re inspired by Zora Neale Hurston’s (BC 1928) 1933 “Characteristics” essay, where she lays out different elements that you see across African American dance, theater, and music.

Zora—a pivotal figure during the Harlem Renaissance—mentions things like asymmetry, ornamentation, and personal storytelling. We put our own spin on them and created Jazz Power Tools, which are 13 characteristics that include the stomp clap, shuffle, call and response, cosigning, improvisation, polyrhythm, and reharmonization.

At Jazz Power Initiative, we primarily focus on voice-centric music education. We teach our students the voice is the primary instrument because everybody has a voice. We have great educators like singer Antoinette Montague—our lead voice teacher—who is a legend in Newark, was nurtured by greats like Carrie Smith and Etta Jones, and carries a great African American jazz tradition.

We also work with Charenee Wade, who is an award-winning singer and fantastic voice teacher. We really look for artistic collaborations with like-minded folks who center African American culture as a model of excellence and as a guide for how to make great music.

We’re also very big on intergenerational mentoring, and that stems from my early experiences with Amiri—who founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School in Harlem—and Walter Perkins, who both saw potential in me and nurtured me.

Can you talk about the importance of community partnerships? How has the Jazz Power Initiative collaborated with the West Harlem Development Corporation?

Since we’re a small organization, we have limited physical space for our programs, so we often team up with other local nonprofits and venues. We’ve fostered great, ongoing collaborations with United Palace, Northern Manhattan Arts Alliance, and the Alianza Dominicana Cultural Center. We’ve also had a longstanding partnership with the National Jazz Museum in Harlem, where we’ve been presenting an intergenerational jazz program since 2017. They’ve been a treasure to work with.

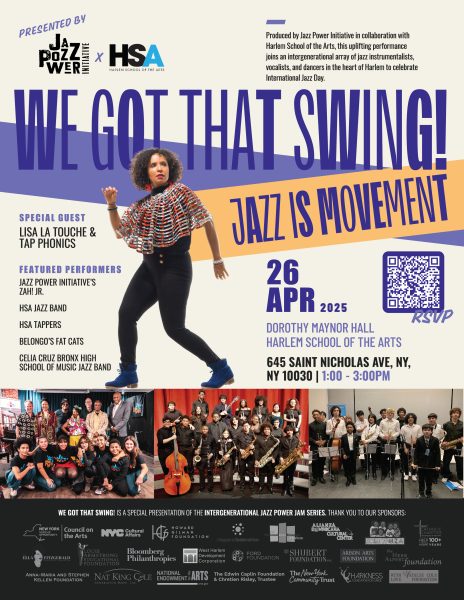

A few years ago, I connected with Harlem School of the Arts through the West Harlem Development Corporation. I had been a huge fan of the school and had taken my daughter there for dance classes. HSA’s then-chief education officer, W. Lee Hogans—who is a wonderful trumpeter and educator—and I collaborated on an annual program called We Got That Swing. It’s all about celebrating youth involvement in jazz, and we involve as many Uptown kids as possible. We’ve done it three years in a row and have had participation from the Celia Cruz Bronx High School of Music’s band, members of the Afro Latin Jazz Alliance’s Belongó, and Harlem Samba. We will present the next one at HSA on Saturday, April 18, 2026.

Through the partnership with HSA, we unite our ensembles and have them participate in an International Jazz Day global stream every April.

It’s really important for kids to see each other being involved in and loving jazz. It’s a wonderful partnership, and we appreciate the support of the West Harlem Development Corporation to keep it going.

What’s on the horizon for the Jazz Power Initiative?

We’re going to continue our Jazz Power Institute for artists and educators. Through the program, New York City Department of Education teachers can get Continuing Teacher and Leader Education (CTLE) credit hours. Last year, we had Sweet Honey in the Rock’s founding members Carol Lynn Maillard and Louise Robinson; tap dance artist and choreographer Lisa La Touche, who was in Shuffle Along on Broadway; trumpeter Jeremy Pelt; and our vocal teacher Charenee Wade. This year’s institute is focused on voice and tap dance.

We’re also focused on expanding our weekly low-cost adult education workshops on Tuesdays in Inwood—inspired by the late jazz pianist Barry Harris, who led incredible community-facing workshops for years—where we focus on piano, voice, and improvisation, and learn a new jazz standard every week.

We have a lineup of exciting community concerts on the horizon. In October, we commissioned a piece to celebrate saxophonist Claire Daly, who passed away last year. In November, we’re going to showcase the Lulada Club, an all-women salsa band. In December, our focus will be on intergenerational voices.

Next January, we want to organize an all-day celebration to honor the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. In the Spring, we’ll perform our Nora’s Ark, the jazz musical at Lehman College in the Bronx. We’ve also developed a new partnership in Inwood with the Activities, Culture, and Training (ACTS) Center at The Eliza. It’s a newly constructed affordable housing space—built on top of the Inwood Library—that offers cultural and educational programming.

Carol Maillard, Charenee Wade, Louise Robinson

Carol Maillard, Charenee Wade, Louise Robinson

“It’s a very freeing space to be in and have a cathartic experience through the use of jazz.”

“It’s a very freeing space to be in and have a cathartic experience through the use of jazz.”